There is a lie we tell ourselves when we hit the "past tutorial phase" status. We pretend we have finally achieved that mythical "deep understanding" of our tools. We imagine a day when our browser history contains only thoughtful queries about distributed systems and ergonomic keyboard layouts.

That day never comes.

This week, between reviewing auth flows (something I wrote about recently) and fighting with CSS transitions for a new project, I found myself staring at a blinking cursor, typing the same six queries I have typed a hundred times before.

Here is my confession.

Git Stash: Pop vs. Apply vs. "Where Did My Code Go?"

I love git stash like I love my coffee maker. I use it every morning without thinking, and occasionally I break something by pressing the wrong button.

This week I stashed some experimental changes to work on a hotfix. Two hours later, I wanted those changes back, but I couldn't remember if I should pop them or apply them. Both commands bring your code back, but one of them is a ticking time bomb.

Here is the difference, once and for all:

# Brings changes back but KEEPS the stash in the list

git stash apply

# Brings changes back and DELETES the stash (like cut and paste)

git stash pop

# Deletes the stash without applying it (the 'oops' button)

git stash drop stash@{0}

The apply command is for when you are paranoid (which should be always). Maybe the stash won't merge cleanly. Maybe you want to apply it to multiple branches. Apply leaves the stash sitting in your git stash list like a safety net.

Pop is for when you are done. It applies the changes and immediately runs git stash drop behind the scenes.

Pro tip: If there are merge conflicts when you run

pop, Git gets scared and aborts the deletion. It behaves exactly likeapplyinstead. This has fooled me into thinkingpopfailed, leading me to apply the same stash twice and create a beautiful merge conflict where none existed before. Check the Git docs if you don't believe me.

I also learned this week that you can stash specific files with git stash push -m "my message" path/to/file, which creates a named stash. But I will forget that by next week, so we are back to git stash apply.

Deleting Git Tags: Local vs. Remote (The Two-Step Dance)

Tags are supposed to be permanent. That is the point. They mark releases, milestones, the "we shipped it" moments. But sometimes you fat-finger a tag name, or you realize you tagged the wrong commit because you were trying to finish work before lunch.

Deleting a tag requires two separate operations because Git treats your local repository and the remote as two distinct kingdoms that barely talk to each other.

# Delete locally (this is the easy part)

git tag -d v1.0.0

# Delete remotely (this syntax is weird)

git push origin :refs/tags/v1.0.0

# Or the newer, clearer syntax

git push -d origin v1.0.0

That colon syntax in the first remote example (:refs/tags/v1.0.0) is ancient Git magic. It means "push nothing to this reference," effectively deleting it. It looks like a typo. Every single time I have to do this, I Google it to make sure I am not about to push an empty branch named refs/tags/v1.0.0 and destroy production.

If you have multiple tags to delete, you can chain them or use pattern matching, but honestly, just delete them one by one. Deleting tags in bulk feels like defusing a bomb. You want to go slow.

Go Maps and the Comma-Ok Idiom

I write a lot of Go. I have built authentication services, CRM tooling, and screen capture utilities in Go. You would think I have internalized the basics by now.

You would be wrong.

In Go, checking if a key exists in a map uses something called the "comma ok idiom." It looks like this:

user, ok := users["george"]

if ok {

// The key "george" exists

fmt.Println(user.Email)

} else {

// Key doesn't exist, user is the zero value (nil/empty string/0)

fmt.Println("User not found")

}

The reason this exists is that Go maps return the zero value for the type when you access a missing key. If users is a map[string]User, accessing users["invalid"] gives you an empty User struct, not an error, not a nil pointer. Just a hollow husk of a user with empty strings and zeros.

Without the ok check, you might process that empty struct thinking it is valid data. I have done this. I have introduced bugs that returned blank email addresses to the frontend because I forgot to check if the user record actually existed in my cache before using it.

The comma-ok idiom is elegant once you know it, but the syntax refuses to stick in my brain. I always want to write if users["george"] != nil like I would in Python or JavaScript. But Go doesn't work that way. It wants to be explicit. So I Google it, copy the pattern, and move on until the next time I need it.

Package.json: Type Module vs CommonJS (The Eternal Migration)

JavaScript is going through an identity crisis that has been ongoing for roughly five years. We are trying to move from CommonJS (require and module.exports) to ES Modules (import and export), but the transition is messy. Every new Node.js project starts with the same ritual: create a folder, run npm init -y, then immediately Google which type field to use.

Here is the breakdown I keep needing to reference:

// For CommonJS (the old way, still default if you omit "type")

{

"type": "commonjs"

}

// For ES Modules (the new way, requires .js files to use import/export)

{

"type": "module"

}

If you set "type": "module", every .js file in your project is treated as an ES Module. You can use top-level await, static imports, and all the modern syntax. If you leave it as CommonJS (or omit the field entirely), you are stuck with require and dynamic import() expressions.

The pain point comes when you mix them. Some older npm packages only export CommonJS. Some tools expect ES Modules. You end up with .mjs and .cjs file extensions flying around like shrapnel.

Why I keep Googling this: The error messages are confusing. If you try to use

importin a CommonJS project, Node throwsSyntaxError: Cannot use import statement outside a module. If you try to userequirein an ES Module project, it fails differently. I always second-guess which one I am in, especially when jumping between legacy codebases and greenfield projects.

Read the official Node.js docs on package.json type fields if you want the full gritty details on how the module resolution algorithm works. It is fascinating and slightly terrifying.

How to Exit Vim

I am going to say something controversial: opening Vim accidentally is not a badge of honor. It is not a "skill issue." It is a design failure that we have normalized for thirty years because Unix nerds think suffering builds character.

Here is what happens to me. I type git commit without the -m flag. Git launches my default editor, which is Vim because I set it six months ago during a terminal customization phase and immediately forgot how to change it. Suddenly my terminal looks like this:

~

~

~

~

~

~

"some-file.txt" [noeol] 1L, 4B

Nothing works. Ctrl+C beeps at me. Ctrl+D does nothing. The Escape key seems to do something, but then I press q and it just types the letter "q" at the bottom of the screen.

Here is the escape hatch:

:q " Quit (only works if you haven't changed anything)

:q! " Quit without saving (the panic button)

:wq " Write (save) and quit

:x " Same as :wq but slightly shorter

:qa! " Quit all buffers without saving (nuclear option)

Important: You must press Escape first to get into "normal mode" before typing the colon. If you do not, you are just typing text into the document. The colon only works in normal mode.

The ! symbol in Vim is the "force" flag. It overrides warnings. :q will refuse to close if you have unsaved changes. :q! says "I don't care, destroy my work, get me out of this nightmare."

There is also ZZ (capital Z, twice) which saves and quits in one keystroke from normal mode, but I always forget that one exists because it looks like a typo.

I should probably switch my $EDITOR to nano or just use git commit -m "message" forever, but the sunk cost fallacy keeps me trapped in Vim purgatory.

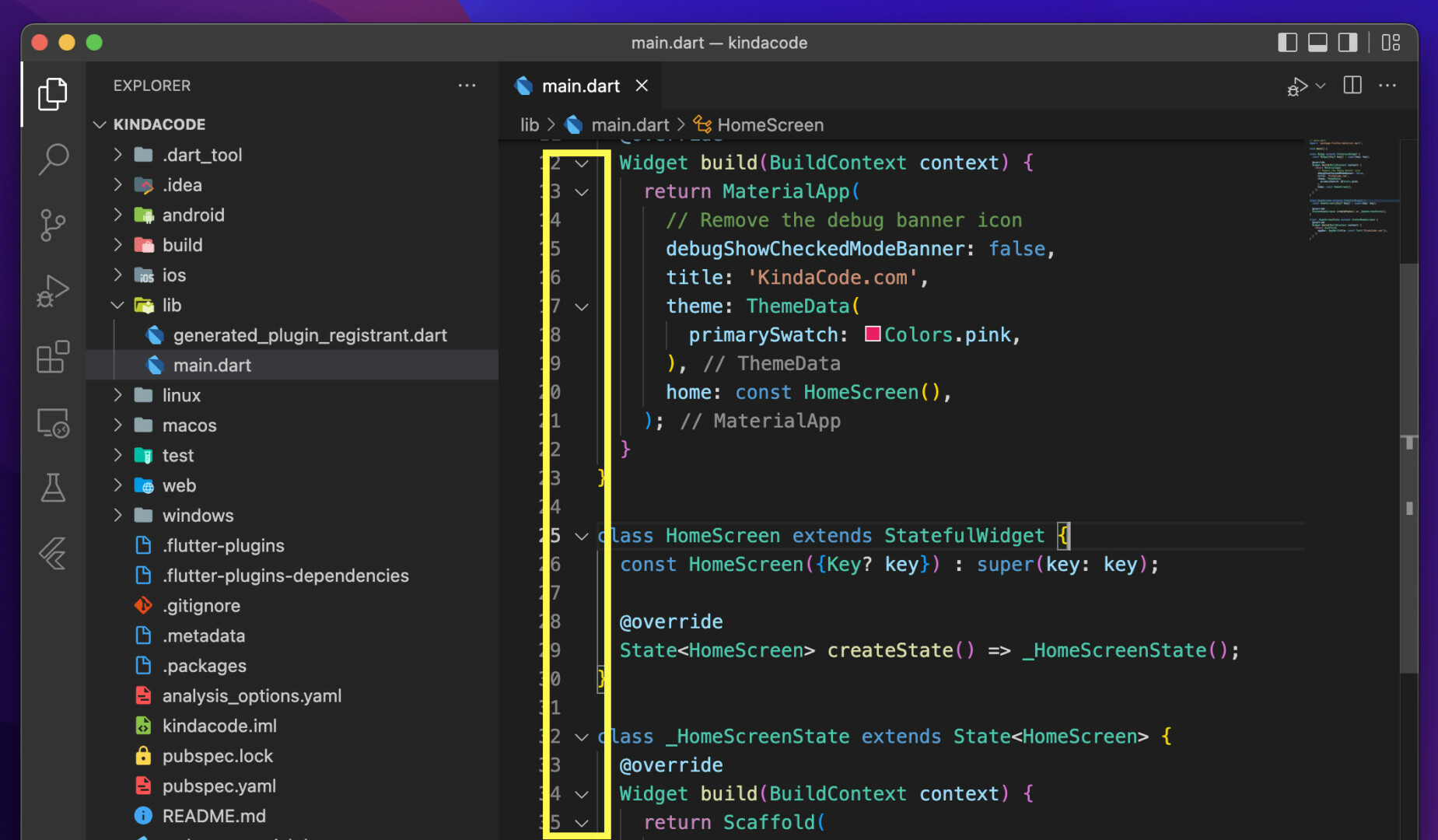

VS Code: Collapse All Functions

I work with large codebases. When I open a new Go file with eight methods, four interface implementations, and three struct definitions, I want to see the shape of the code before I dive into the details. I want to collapse everything and see only the function signatures, like a table of contents.

VS Code has folding, but the shortcuts are not intuitive. They involve chorded key combinations (pressing multiple keys in sequence) that feel like playing DDR with my fingers.

Here is the incantation:

# Windows/Linux

Ctrl + K, Ctrl + 0 (zero, not O)

# macOS

Cmd + K, Cmd + 0

# To unfold everything

Ctrl + K, Ctrl + J (or Cmd + K, Cmd + J on Mac)

You have to press Ctrl+K (or Cmd+K), release it, then press Ctrl+0 or Ctrl+J. If you try to hold them all down at once, it does not work.

There are also level-specific folds:

Ctrl+K Ctrl+1folds to level 1 (top level functions/classes)Ctrl+K Ctrl+2folds to level 2 (includes nested blocks)- And so on...

I use "Fold All" probably ten times a day when exploring unfamiliar code. It helps me understand the architecture without getting lost in the implementation details. But I will never, ever remember that 0 folds everything and J unfolds. My muscle memory refuses to encode it. So I open the command palette (Ctrl+Shift+P) and type "fold all" like a tourist.

The Pattern

There is a common thread here. We do not Google these things because we are bad developers. We Google them because the details are arbitrary. The syntax of Git stash commands is not intuitive architecture; it is historical accident. The Vim exit commands are fossils from an era when keyboards had different layouts. The Go comma-ok idiom is elegant but specific.

What makes us experienced is not memorizing these incantations. It is knowing which incantation we need, and roughly where to find it. I know I need the comma-ok idiom; I just cannot remember if the boolean comes first or second. I know I need to stash pop; I just cannot remember if it deletes the stash automatically.

Engineering is pattern recognition, not syntax memorization. My browser history is a shrine to that truth.

What did you Google this week? Comment. By the way, I have a newsletter, susbscribe